Gambling with Wario on a New Way to Play

There is one game that has me more excited than any other this summer, and that is Nintendo’s Game and Wario.

With Game and Wario, Nintendo is showcasing the sort of games that were not possible before the Wii U: games that let the players themselves be the heroes instead of acting through an abstract character avatar. Taking the Wii’s motion controls a step further, the Wii U’s Gamepad allows Nintendo to experiment with new levels of immersion and augmented reality.

Game and Wario is the latest installment in Nintendo’s long-running WarioWare series. The nature of WarioWare makes it the perfect platform to demonstrate how Nintendo’s recent experiments with gameplay and genre have matured.

Each game in the series is a compilation of bizarre and disorienting microgames, which are the smallest possible units of a game. Each one features one or maybe two commands: in one microgame a skier is sliding downhill and the player needs only to tap the A button to help the skier jump off of the slope; in a fireworks microgame the player needs to tap A to detonate a rocket; and in a fly-swatting microgame the player must tap the touch screen to swat flies.

This reductionist approach to gameplay allows each microgame to be very brief, usually only a few seconds long. It also allows WarioWare to squeeze an enormous amount of gameplay variety into a short period of playtime, challenging the player to pass a gauntlet of microgames that become faster and more difficult as the player progresses. The frantic pace tests the players’ reflexes more than it does their ability to master complex commands, and the brevity and simplicity of each microgame make it easy to slip into a rhythm, or even a trance, while playing. As a result, WarioWare rewards muscle memory and mental calmness more than it does the critical thinking or caution that characterizes so many other, slower-paced games.

This reductionist approach to gameplay allows each microgame to be very brief, usually only a few seconds long. It also allows WarioWare to squeeze an enormous amount of gameplay variety into a short period of playtime, challenging the player to pass a gauntlet of microgames that become faster and more difficult as the player progresses. The frantic pace tests the players’ reflexes more than it does their ability to master complex commands, and the brevity and simplicity of each microgame make it easy to slip into a rhythm, or even a trance, while playing. As a result, WarioWare rewards muscle memory and mental calmness more than it does the critical thinking or caution that characterizes so many other, slower-paced games.

Every game in the WarioWare series has experimented with new ways for the players to interact with it. For instance, Mega Microgame$! (GBA, 2003) invites players to forget everything about playing games and to let the game flow through them. Twisted! (GBA, 2005) incorporates a gyroscope, asking players to physically rotate their Game Boy to play. Touched! (NDS, 2005) uses touchscreen gestures to interact with the game, and Smooth Moves (Wii, 2007) uses Wiimote gestures. Snapped! (DSiWare, 2009) uses the DSi camera to track players’ facial movements and add their image to the game. D.I.Y. (NDS, 2010) allows players to create their own microgames. For the most part, this series has made physical demands on players. To play WarioWare, it is not enough to press buttons and flick a joystick; players must become physically involved with the game and let it turn into an extension of themselves, often using the console, remote, or their own bodies to mime the actions that are performed in-game.

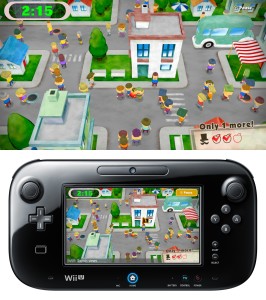

The trailer for Game and Wario demonstrates many of these experiments at work. According to the trailer there will be 16 short games in the final release. I want to focus on a few of them that show how the players, through their actions with the Gamepad, actually stand in for the in-game characters.

The trailer for Game and Wario demonstrates many of these experiments at work. According to the trailer there will be 16 short games in the final release. I want to focus on a few of them that show how the players, through their actions with the Gamepad, actually stand in for the in-game characters.

In “Gamer”, the character 9-Volt will be on the TV screen, playing his Game Boy in bed when he is supposed to be sleeping. Players will use the Gamepad itself as 9-Volt’s Game Boy, playing a series of microgames. Like 9-Volt, players can’t blink while playing these fast-paced games, and they must watch the TV to make sure that his mother doesn’t catch him and make him go to sleep.

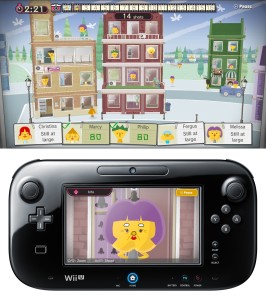

“Shutter” is a game in which the player will need to catch criminals by photographing them. Unlike older photography games, such as Pokémon Snap or Fatal Frame, which use traditional controllers to move a virtual camera, players will use the Wii Gamepad itself as a prop camera. “Shutter” is the game that most strongly catches my attention.

This isn’t Nintendo’s first foray into photography gameplay. Nintendo has played with virtual cameras in major titles of previous generations, such as the pictobox item in The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker. The aforementioned Pokémon Snap is a Nintendo 64 title that revolves around a photographic tour of a Pokémon island: instead of capturing Pokémon with balls, the player captures them on film.

Nintendo has not been alone in playing with virtual cameras: in Ubisoft’s Beyond Good and Evil (2003), the heroine is a photographer investigating a conspiracy; in Tecmo’s Fatal Frame (2001), the heroine uses a special camera to photograph and exorcise spirits. However, with the exception of a few minor experimental titles like Warioware Snapped!, these games were limited by the controls of the consoles. Players did not really use the controller as a camera, but instead issued abstract commands by pressing buttons and joysticks on the face of the controller.

The new technologies of the current-generation systems are finally allowing these experiments to grow. Spirit Camera (3DS, 2012) has already established a new genre of photography games. In this title jointly developed by Nintendo and Tecmo, players look through the 3DS camera to see ghosts emerging in the space around them. The game world and the real world are integrated seamlessly, so that the 3DS acts as the eponymous Spirit Camera. The player is no longer abstracted from the main character and their Camera Obscura: the player is holding the Camera Obscura; the 3DS is the camera and the player is the heroine.

The Wii U’s Gamepad combines all of the input devices that Nintendo in general and WarioWare in particular have been experimenting with. Game and Wario demonstrates that, for Nintendo, hardware does not come before software. The hardware is designed to allow developers to create the kinds of games that they could not make without it. The Wii U’s unique controller has been chosen to take Nintendo’s experimental projects from the sidelines and push them into the spotlight. I look forward to seeing how well Game and Wario exploits this novel peripheral.

About This Post